Lawyer TikTok? Yes, It’s a Thing.

By Barbara Engstrom, Executive Director King County Law Library

An article titled “How Lawyers Can Benefit from TikTok Without Being ‘Cringe’”[1] recently came across my inbox. My first thought was: Wait, how does a lawyer even have a professional presence on TikTok? From my limited exposure to TikTok via my teenagers, it is primarily teens posting dance videos and responding to odd ball challenges. Granted, kids spend hours swiping through TikTok content, but that demographic doesn’t seem likely to generate many client leads.

My second thought was: How can anyone over the age of 20 avoid being “cringe?” I am regularly labeled cringe for my choice of food, clothing, music, and car (2007 Subaru wagon). But TikTok is a fickle mistress. Case in point, the New York Times recently ran piece on 52-year-old documentary filmmaker, Louis Theroux’s sudden rise to TikTok fame based on his rap “Jiggle Jiggle.” “He delivers the rap in an understated voice that bears traces of his Oxford education, giving an amusing lilt to the lines ‘My money don’t jiggle jiggle, it folds/I’d like to see you wiggle, wiggle, for sure.’”[2]

How is TikTok Different from other Social Media?

First, TikTok is for very short attention spans. Videos are often 15, 30, or 60 seconds. Recently, the maximum time was expanded from 3 minutes to 10 minutes but apparently anything over 1 minute “stresses users out” and users will watch longer videos at double speed.[3] Second, unlike other social media where you need to build up a significant base of followers to gain viral status, TikTok’s algorithm allows creators to go viral with few to no followers making it less of a barrier to entry for those first starting out. Third, TikTok is very, very popular. It was “the most downloaded app of 2021 and boasts more than a billion monthly active users. Mobile researcher Data.ai estimates that the average user spends nearly twice as much time on TikTok every month as they do on Facebook – 28.7 hours, compared to 15.5 hours.”[4]

How are Lawyers Using TikTok?

Some lawyers like Cecillia Xie of Morrison & Foester, Joanne Molinaro of Foley Lardner and Fumnany Ekhator, a recent Penn Law grad, use TikTok to discuss the law but more in connection with their personal lives.[5] Clothes, food, and relationships get blended into posts about the law school experience or what it’s like to practice law. Other attorneys use TikTok as a medium to give legal information in a bite-size, entertaining format as a marketing and outreach tool. Mike Mandell, lawbymike, uses goofy videos to describe basic concepts of criminal law like police stops or spousal privilege. Ethen Ostroff, “The TikTok Lawyer” has videos geared to other attorneys – grow your business on social media; using virtual assistants – as well as videos aimed at potential clients – boating accidents; CPAP machine side effects. Brad Shear, bradshear, does very short legal takes on current events. Maclen and Ashleigh Stanley, the.law.says.what., married recent Harvard Law grads, do slightly longer explainers on current news stories.

What are the Upsides?

Cecillia Xie makes a compelling case for the upsides of attorneys on TikTok and mentions the following ways that creating a presence on TikTok can be a smart move. 1. “Creating content on TikTok can raise your profile. Early adopters of any social media platform tend to reap outsize rewards compared to later adopters. As the creator pool becomes more saturated over time, it becomes increasingly difficult to stand out and effectively reach your target audience. Take advantage of TikTok’s relative nascency and current momentum while you can.”[6] Case in point, most of the articles that come up in a search for lawyers on TikTok either feature or at least mention one Cecillia Xie. 2. “Being one of the first to interface with a consumer product like TikTok can help you develop familiarity with its technological features and better understand the competitive landscape facing your clients.”[7] As TikTok continues to dwarf Twitter and Snapchat in advertising market share, it is likely that more potential clients will be using TikTok and working knowledge of the vagueries of TikTok can prepare one for future client issues. 3. “Compelling branding on TikTok can deepen your relationships with clients…. With the press of the record button, TikTok allows you to showcase your personality and knowledge simultaneously – a hybrid short-form power lunch and client alert distributed to as many people as are on your mailing lists, or more. And even if all of your clients are not on TikTok, their kids definitely are.”[8]

What are the Pitfalls?

Leila Bijan of Zuckerman Spaeder noted six ethical pitfalls for lawyers on TikTok. They include:

- Inadvertently creating attorney-client relationships with followers – Many lawyers on TikTok offer advice on what their followers should do in different types of legal situations, such as police encounters. If the advice is specific enough, it could create an attorney-client relationship…

- Revealing client confidences – Lawyers who want to discuss interesting clients and cases on TikTok are playing with fire, since—subject to a few exceptions—lawyers are prohibited from revealing information about the representation of a client….

- Getting caught up in TikTok trends and entertainment value at the expense of your ethical obligations — Anything that combines humor or sarcasm with legal advice should be approached with extreme caution….

- Providing inaccurate legal information — Lawyers on TikTok should be crystal clear about the jurisdictional limitations to their legal commentary….

- Making a lawyer advertisement that does not meet ethical requirements — Some lawyers on TikTok discuss past case successes, including the large verdicts they’ve won for their clients. But slight variations in wording can turn a lawyer’s celebration of success into a lawyer advertisement that might not comply with the relevant lawyer advertisement rules ….

- Not knowing which jurisdiction’s ethical rules govern or what those rules are — If a lawyer reaches audiences beyond state lines (which is likely on such a popular platform), then that lawyer might be subject to those jurisdictions’ rules too—even if the lawyer is not an admitted member of those bars.[9]

How to Avoid Being “Cringe”

For those attorneys who successfully navigate a professional presence on TikTok, or any social media platform for that matter, a delicate balance between creating content that is entertaining, informative, and a bit whimsical is de rigueur. Cecillia Xie suggests using a deep understanding of your audience and your brand to guide your content, along with mirroring the tools and effects that other trendsetters are using to create compelling content. “TikTok may feel casual, but posting publicly is anything but. Before you post a video, always ask yourself whether you would be comfortable playing the video in Times Square or appearing as a headline in the New York Times.”[10] Ethen Osstroff also has some advice for success on TikTok. He notes that self-promotion will backfire. “Think ‘reach out to me for questions’ instead of ‘contact a lawyer.’” He also advises not to get overly caught up in reactions to the videos – people are bound to judge – just focus on putting up content with value. [11]

A “Second Life” Cautionary Tale

Having looked at a bit of the attorney TikTok content I would have to say that my reaction is a solid “meh.” TikTok is created for short attention spans, the law is not. To me, a lot of the content made my ethics violations radar go “jiggle jiggle.” Compelling TikTok videos also seem to require a lot of exposition of one’s personal life. I imagine it’s a difficult dance to balance that level of personal exposure with maintaining a professional demeanor.

On social media, a premium is placed on coming up with new, ever-evolving content. For attorneys who are already overscheduled, the sheer amount of time it takes to create, review, and distribute content seems like a poor return on investment. I’m reminded of the hype surrounding Second Life in the mid-2000s. Many a university spent significant resources building a presence on Second Life with replicas of their real-life campuses and virtual classrooms where actual, for-credit classes were taught. Second Life’s popularity fizzled before long, leaving those virtual campuses ghost towns.

But then again, what do I know? I could never have imagined why anyone would want to use Twitter and I still read books in print, which I’m pretty sure is “cringe.”

Questions on TikTok or Other Social Media?

If you have questions on using social media to market your practice, how social media fits into the rules of professional conduct, or how social media has been handled by courts feel free to contact the King County Law Library at services@kcll.org. We are also happy to help with non-trendy (re: cringe) research topics as well.

[1] Cecillia Xie, How Lawyers Can Benefit from TikTok Without Being ‘Cringe’ Law 360 (July 25, 2022) https://www.law360.com/articles/1514743

[2] Stephen Kurutz, How Louis Theroux Became a ‘Jiggle Jiggle’ Sensation at Age 52, New York Times (June 17, 2022) https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/17/style/louis-theroux-jiggle-jiggle-tiktok.html

[3] Chris Stokel-Walker, TikTok Wants Longer Videos – Whether You Like It or Not, Wired (Feb 21, 2022) https://www.wired.com/story/tiktok-wants-longer-videos-like-not/

[4] See Xie supra

[5] Tianna Headley, Big Law’s TikTok Stars Embrace Industry’s New Social Media Norms, Bloomberg Law (July 12, 2021) https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/big-laws-tiktok-stars-embrace-industrys-new-social-media-norms

[6] See Xie, supra

[7] Id

[8] Id.

[9] Leila Bijan, Six Ethical Pitfalls to Avoid on Lawyer TikTok, JDSupra (Sept 30, 2021) https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/six-ethical-pitfalls-to-avoid-on-lawyer-9601327/

[10] See Xie, supra

[11] Jacob Sapochnick, 11 Lawyers Going Viral on TikTok Right Now, Enchanting Lawyer, https://www.enchantinglawyer.com/10-lawyers-going-viral-on-tiktok-right-now/

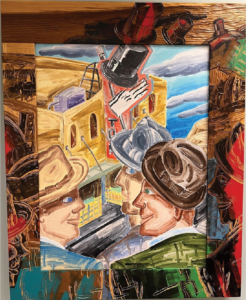

When you first walk into the library and look to your left, you’ll see a large colorful piece by Patrick Siler called The Meeting. This lithograph depicts three men wearing hats gathered. This piece is interesting in that the frame isn’t just a frame but is part of the art. The frame is carved and extends the scene depicted. This is probably the most colorful of the pieces in the library.

When you first walk into the library and look to your left, you’ll see a large colorful piece by Patrick Siler called The Meeting. This lithograph depicts three men wearing hats gathered. This piece is interesting in that the frame isn’t just a frame but is part of the art. The frame is carved and extends the scene depicted. This is probably the most colorful of the pieces in the library. Near the state Supreme Court Briefs, you’ll find a painting of a teacup waiting to be filled by the steaming blue and white jug and maybe a cherry as a sweet treat. This painting, titled Jug, was done by local husband and wife duo Julie Paschkis & Joe Max Emminger. Though each artist has their own style they were able to collaborate and create a piece that looks seamless

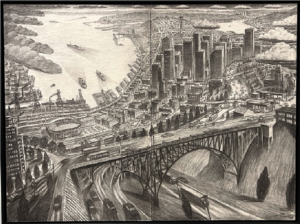

Near the state Supreme Court Briefs, you’ll find a painting of a teacup waiting to be filled by the steaming blue and white jug and maybe a cherry as a sweet treat. This painting, titled Jug, was done by local husband and wife duo Julie Paschkis & Joe Max Emminger. Though each artist has their own style they were able to collaborate and create a piece that looks seamless Finally, I want to draw your attention to a few pieces that are tucked away in conference rooms. The first, a charcoal drawing by Douglas Cooper, can be found in our Legal Research and Training Center. Mr. Cooper is also responsible for the murals on the first floor of the courthouse. The drawing is called South Seattle Bridge and depicts the Jose Rizal Bridge looking towards Elliott Bay. In conference room one, you’ll find a Brad Brown piece called Third Drift 46-54 which is made up of nine squares that are composed of different torn pieces of paper. In conference room six there’s a photo of a fountain surrounded by a fence with what looks to be signs leaning against it. Fountain #1 by Jeff Krolick reminds me of a reflecting pool where you might want to sit and enjoy the sunshine for a bit.

Finally, I want to draw your attention to a few pieces that are tucked away in conference rooms. The first, a charcoal drawing by Douglas Cooper, can be found in our Legal Research and Training Center. Mr. Cooper is also responsible for the murals on the first floor of the courthouse. The drawing is called South Seattle Bridge and depicts the Jose Rizal Bridge looking towards Elliott Bay. In conference room one, you’ll find a Brad Brown piece called Third Drift 46-54 which is made up of nine squares that are composed of different torn pieces of paper. In conference room six there’s a photo of a fountain surrounded by a fence with what looks to be signs leaning against it. Fountain #1 by Jeff Krolick reminds me of a reflecting pool where you might want to sit and enjoy the sunshine for a bit.